How to tell if an online article is real, fake or a scam

Posted on

by

Kirk McElhearn and Derek Erwin

Fake news, scams, and phishing are the plague of our times. It’s getting increasingly difficult to determine which websites are presenting truthful information. I’m not just talking about political views; people can disagree about those, and while you may not like what you read on certain sites, that doesn’t mean, as some like to say, “it’s fake news.”

A Stanford University study of 7,804 students from middle school through college found that some 82 percent of them cannot distinguish between an ad labeled “sponsored content” and a real news story on a website. These findings present a real risk when visiting websites you’re not familiar with; and, not just for students, for everyone. How can you know if what you’re reading online is telling the truth or trying to scam you either directly—such as by trying to sell you something, or get your personal information—or indirectly, by spreading lies, or by sowing doubt?

In this article, we offer a few tips to help you sort the wheat from the chaff on the Internet. These tips will help you determine if an online article is real, fake or a scam.

Do you recognize the publication name?

There are publication names you may recognize, and that you can trust — they may be the major news organizations, such as the New York Times, Forbes or The Wall Street Journal, or even familiar household brands that you know.

However, there may be some websites that try to suggest that they belong to a brand. For example, apple-hot-deals.com (this site does not exist, right now) might try to pretend that it’s an Apple website, but it’s most likely not. Most brands don’t use compound domain names in this way, which anyone can register; instead, they use URLs such as apple.com/hotdeals (this also doesn’t exist).

Here at The Mac Security Blog, we use the intego.com domain, and the blog is hosted at www.intego.com/mac-security-blog/, proving that it belongs to Intego’s domain.

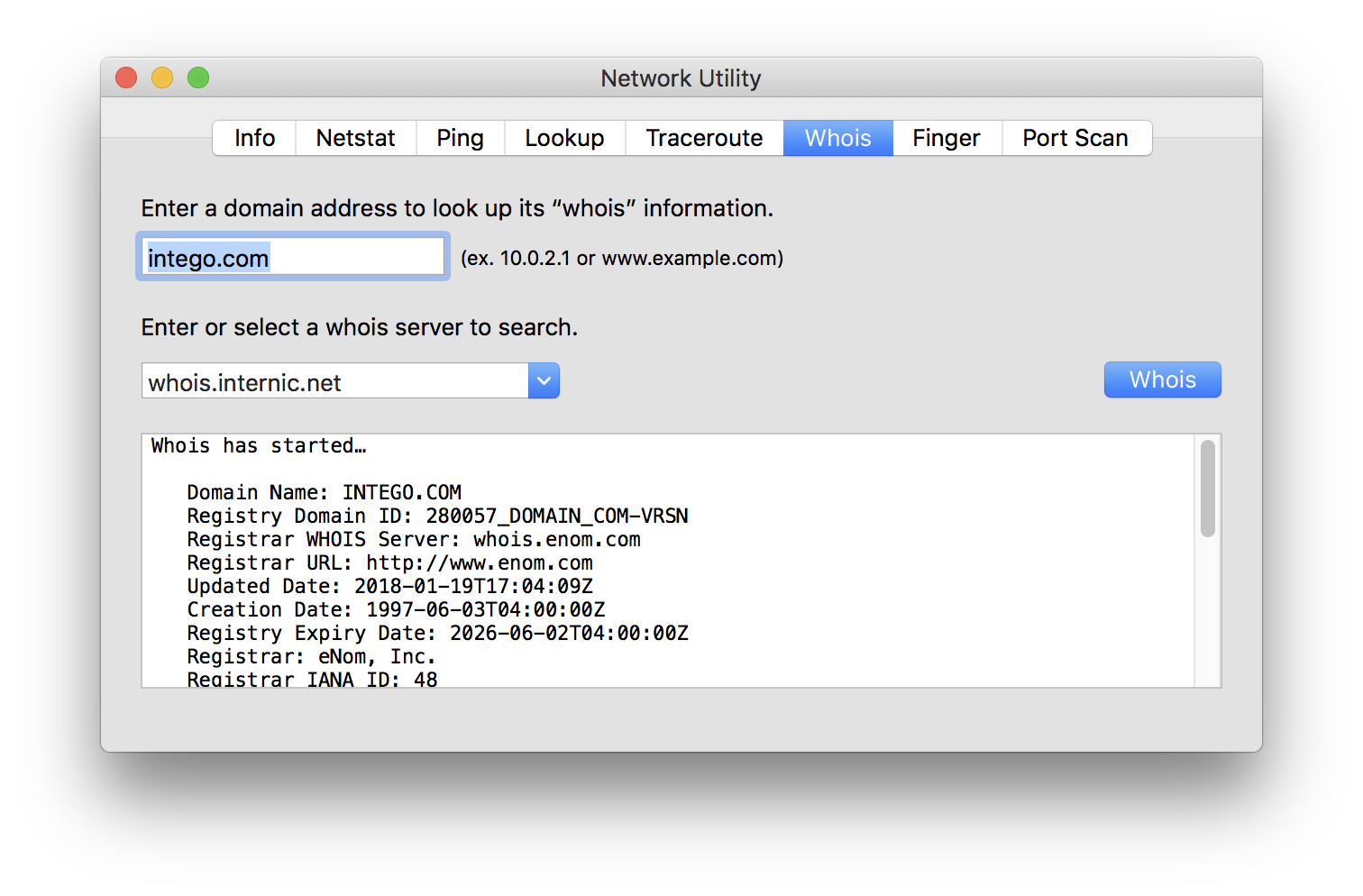

You can check how long a domain has existed by using a command called “whois.”

On older versions of macOS, if you were to go to the top level of your Mac’s disk, then navigate to /System/Library/CoreServices/Applications (or on even older macOS versions, /Applications/Utilities), you would find an app called Network Utility. If you then launched the app, you could paste a domain copied from your browser’s address bar, such as intego.com, into the Whois tab:

Starting with macOS Big Sur, the Network Utility has been deprecated, so you’ll now have to open the Terminal (in /Applications/Utilities) instead, and type “whois” followed by a space, then paste the copied domain.

When you run the whois query, you’ll see when the domain was first registered (in Intego’s case, the Creation Date is in 1997), which can serve as evidence of how long the company has been around.

This isn’t a guarantee that a site hasn’t transferred ownership since it was first registered, nor does it indicate whether a site may have been hacked, but seeing how long ago a domain was registered can be a basic step toward confirming a site’s possible legitimacy. Scam sites often, though not always, use recently registered domains.

Is the information from a secure site?

Most websites should be secure these days. Look in the address bar of your browser, and you should see a padlock. This means that the connection to the intego.com website (for example) is secure, using HTTPS. The intego.com domain has a TLS/SSL certificate, which helps ensure that when you type intego.com, your browser is showing you information served by Intego (as opposed to a theoretical man-in-the-middle attacker).

This said, anyone can purchase an SSL certificate for any domain they own, but the lack of HTTPS security is something to be wary of. (RELATED: 6 Cyber Security Tips to Ensure a Website is Secure.)

Are you able to contact the site owner or company?

Legitimate websites nearly always have a Contact section featuring an email address, a form, or some other way to get in touch with the site’s maintainers. Most business sites should also have one or more postal addresses of offices, and a phone number. Again, this isn’t hard and fast proof of legitimacy, but if you try to contact the company and find that a real person replies, this can at least help you confirm that someone is vouching for it.

Businesses in the United States may show up on the Better Business Bureau website. You won’t find every business there, but you will find reviews for some businesses.

Did you run a search on it?

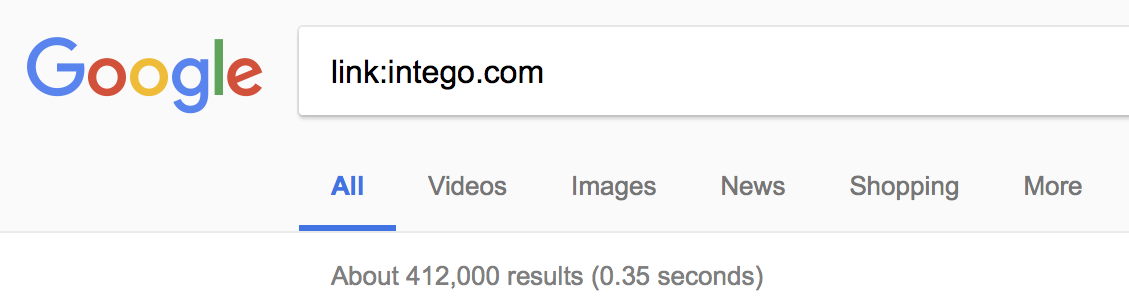

You can check most search engines to find information on just about anything, and you might want to try searching for a company or publication that runs the site you’re curious about. You should see their own domain near the top of the list, but one way to see how much of a footprint a company has is to search for links to a company from other sites.

Google used to have a link: search operator, so if you searched for link:intego.com you would get more than 400,000 results of links to pages on the Intego website. Unfortunately, Google killed off the link: operator in 2017. Instead, you can try just searching for the domain or company name whose reputation you’re trying to establish.

Google used to have a link: search operator to help identify authoritative sites that linked back to a domain.

Have you checked the spelling within the article?

Yes, anyone can make miskates and end up with tyops on a wesbite, and anyone can run a spell checker, but scam sites are often set up by people whose native language is not English (or the language of the site you’re visiting), and poor language can be a clue that something is amiss. Similarly, you may also find look-alike characters where you would expect to see English alphabet letters.

Some scammy pages generate their content by scraping text from a legitimate site, and using automated methods to swap out some words from the original with synonyms. Scam pages presumably do this in hopes that search engines won’t punish them with lower search engine rankings for blatantly plagiarizing content from a more popular site. However, this robotic word-swapping often results in awkward sentences that don’t always make sense. If you’ve ever used a thesaurus, you’ll understand why; not every listed synonym for a word is necessarily a perfect fit in every circumstance.

Did you fact-check the story?

You can generally trust the more authoritative websites to be honest and accurate, especially if they routinely offer corrections to address errors when they find them. The established newspapers, the well-known magazines, and the TV networks that have been around for a long time have traditionally been fairly trustworthy when it comes to reporting facts (at least when it comes to non-partisan, widely agreed-upon topics). That said, don’t assume that everything you read, even from known sites, is truthful information; fact-check it first.

Fact-checking a story isn’t always easy, but some topics can be checked on sites like Snopes. This independent fact-checking website roots out bogus ideas and gives clear evidence for its findings. These days, Snopes covers a lot of politics and policy (with a left-leaning bias), but one recent article asks, Is This a Picture of a Snake Found in a Milk Jug? (Spoiler: it’s Photoshopped.) Historically, Snopes has been a good way to find out if those forwarded e-mails or memes that spread on social media are true or not.

While fact-checking a story sounds simple enough, a 2016 Rasmussen poll found that 62 percent of American voters believed fact checkers are biased. James Taranto, an editor at the Wall Street Journal, actually tweeted that fact-checking “is opinion journalism pretending to be some sort of heightened objectivity.”

"Fact checking" is opinion journalism pretending to some sort of heightened objectivity. Very bad for journalism. https://t.co/LqojbRrN8Z

— James Taranto (@jamestaranto) September 25, 2016

So how do you know who to trust? Can you believe everything you read from just one site? Few publications are wholly balanced, and bear in mind that the opinion and editorial sections of websites and publications are not meant to be such; instead, they are meant to present the individual opinions of columnists and authors.

The best way to spot fake news is to read widely, and not just in a silo of websites or publications that echo your beliefs. Of course, it’s important to find the right sources for your reading. If you’re a liberal, find conservative websites that aren’t virulent or sensationalist, and if you’re a conservative, do the same for liberal-leaning publications. AllSides has a helpful Media Bias Chart that shows how various news media outlets tend to fall on political issues.

AllSides also publishes a Fact Check Bias Chart that shows where on the political spectrum many popular fact-checking sites tend to fall (with community votes showing to what degree site visitors concur).

A few sites related to the whole “fact checking” genre include:

Fact Check Review: RealClearPolitics (RCP) is a Chicago-based media group of experienced journalists who aim to deliver better, more insightful analysis of the most important news and policy issues of the day. Each week in its Fact Check Review, RCP “watches the watchdog” and offers a review of fact-checking outlets that Facebook uses for guidance. This project reviews only those fact checks bearing on civic and public concern.

Check Your Fact: A very well sourced fact-checking news site produced by the journalists of the Daily Caller, with a non-partisan mission to fact check statements by influencers, as well as reporting by other news outlets.

FactCheck.org: A nonprofit website, funded by the Annenberg Foundation, that identifies as a non-partisan “consumer advocate for voters.” Its mission is to reduce the level of deception and confusion in U.S. politics.

PolitiFact: Acquired by the Poynter Institute in 2018, PolitiFact utilizes reporters and editors from the Tampa Bay Times and affiliated media outlets to “fact check statements by members of Congress, the White House, lobbyists and interest groups.” They publish original statements and their evaluations on its website, and assign each a “Truth-O-Meter” rating. (Note: left-leaning political bias)

WaPo Fact Checker: The Washington Post is a news media organization headquartered in Washington DC, purchased by Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos in 2013. Its editorial team publishes a “weekly review of what’s true, false or in-between in politics.” It’s known for its “Pinocchio” ratings. (Note: left-leaning political bias)

Media Research Center: A research and education organization, and product of NewsBusters, that identifies as a premier media watchdog with a mission to “expose bias in the news media and popular culture.” It recently launched a project to fact check the myriad of fact-checking organizations that are relied on by news organizations and social media companies to verify factual claims in news stories. (Note: right-leaning political bias)

Full Fact: A UK-based, independent fact-checking organization, launched in 2009, which aims to “promote accuracy in public debate.” Full Fact is widely considered as a well regulated, strongly sourced, thorough fact-checker.

If you’re looking up information about health or medical conditions, this is particularly sensitive, and the best way to verify claims is to check PubMed, a website run by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) that publishes peer-reviewed medical research articles. You may find some of these articles difficult to read, but you can use them to fact-check claims you see on wellness and health blogs, product descriptions or labels.

Much of the content on PubMed is only available to subscribers, but there are many articles that you can access in their entirety, and that aren’t written for people only in the medical industry. Bonus tip: you generally only need to read the Abstract section of an article on PubMed, which presents the question it addresses and conclusions.

Bottom line

Always remember there are not necessarily “two sides to every story,” and that false equivalence—presenting dissenting opinions about an issue just to pretend to be balanced—doesn’t guarantee balance. On the contrary, often false equivalence is used to bolster ideas that are false or manipulative.

Ultimately the best way to verify information is to do your own research, seek advice from those you trust, and then make up your own mind. What you do with it is your own business.

Further reading:

- Top 10 Online Scams: Watch Out For These Common Red Flags

- How to Determine if Software and Updates Are the Real Deal

- How to Tell if Adobe Flash Player Update is Valid

How can I learn more?

Each week on the Intego Mac Podcast, Intego’s Mac security experts discuss the latest Apple news, security and privacy stories, and offer practical advice on getting the most out of your Apple devices. Be sure to follow the podcast to make sure you don’t miss any episodes.

Each week on the Intego Mac Podcast, Intego’s Mac security experts discuss the latest Apple news, security and privacy stories, and offer practical advice on getting the most out of your Apple devices. Be sure to follow the podcast to make sure you don’t miss any episodes.

You can also subscribe to our e-mail newsletter and keep an eye here on The Mac Security Blog for the latest Apple security and privacy news. And don’t forget to follow Intego on your favorite social media channels: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()