Apple + Recommended + Security & Privacy

OS X Security: Under the Hood Features That Protect Your Mac

Posted on

by

Kirk McElhearn

When you use your Mac for work or play, you see windows and menus for the apps you use, for settings, and more. But these user-facing features are just a small part of what powers an operating system. In addition to all of the many calculations your Mac makes so your apps can do their work, displaying text and video, there are many under the hood security features that keep you and your data safe.

Over the years, Apple has added a number of robust security features to OS X, some of which you’ve heard of, and some that you might not know about. In this article, below, you will discover the less visible security features in OS X that protect you from hackers and malicious software, and that keep your data safe.

File Quarantine

In 2009, when Apple released OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard, the new operating system included a rudimentary anti-malware feature. While the official name is File Quarantine, people in the security industry tend to call it XProtect, after one of its configuration files, Xprotect.plist. We explained how this works back when it was released. Unlike a true anti-virus, File Quarantine looks for a limited number of very specific types of malware. And it only detects this malware if it’s downloaded to a Mac via Safari or Chrome, received as an email attachment by Mail, or sent via a Messages file transfer (and a few other apps).

The only thing a user sees is a banal setting in System Preferences > App Store. Make sure that Install system data files and security updates is checked to ensure that your Mac updates the File Quarantine exclusion list. If your Mac does detect something nefarious, you’ll see an alert.

Gatekeeper

Added to OS X 10.7.5 and 10.8 (Lion and Mountain Lion), Gatekeeper is a technology that uses code signing to verify the authenticity and integrity of applications you launch on your Mac. Every developer can request a certificate from Apple to “sign their code.” This cryptographic certificate allows OS X to ensure that an app you run is not only from a registered developer, but also that it hasn’t been modified.

There are some limits though. As Apple explains:

“Developer ID signature applies to apps downloaded from the Internet. Apps from other sources, such as file servers, external drives, or optical discs are exempt, unless the apps were originally downloaded from the Internet.”

So you’re protected when you download apps, but not if someone manually installs an app on your Mac, or if you copy it from an external or network drive. And this certificate system can go wrong. In November, Mac users suddenly found they could not launch apps from the Mac App Store, because of an expired certificate.

With Gatekeeper, users have three options. In System Preferences > Security > General, you can choose whether you want your Mac to open apps from the Mac App Store only, from the Mac App Store and registered developers, or from Anywhere, bypassing Gatekeeper entirely. It’s a good idea to choose one of the first two options, though if you test applications, you’ll need to pick the third.

Sandboxing

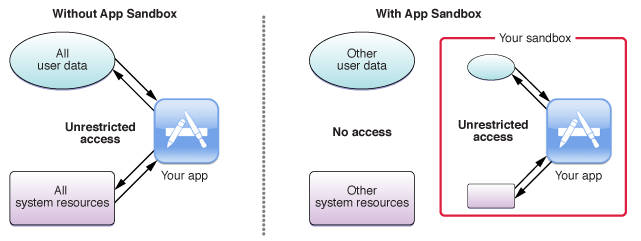

While you may think that sandboxing has something to do with playing or experimenting, it’s actually a robust security feature that was added to OS X 10.5 Leopard, and reinforced with subsequent versions of OS X. Apple says sandboxing “provides a last line of defense against the theft, corruption, or deletion of user data if an attacker successfully exploits security holes in your app.”

Sandboxing is a way of creating a virtual, impenetrable wall around each application or process.

Sandboxing protects Mac users from web-based malware. Since Safari is sandboxed, malware that loads in a web page won’t be able to install on your Mac, or affect other apps or files. However, be wary of anything that downloads unexpectedly, and don’t ever open such files; they could get past the sandbox, if you authorize their installation.

Apple now requires that all apps sold in the Mac App Store be sandboxed, leading to problems with some apps and their features. Sandboxing can limit the way many apps interact with the operating system and with other apps.

For this reason, many developers that sell system utilities do so directly, rather than through the Mac App Store. This is the case, for example, with most of Intego’s software, which needs to be able to access many files on your Mac. You can’t successfully run an anti-virus that can’t check all the files on a computer.

Sandboxing is entirely under the hood, there are no user options or alerts. An app is sandboxed or it isn’t.

Journaled File System

Security isn’t just about protecting you from bad guys, it’s also about ensuring the integrity of your data. One of the unsung security features in OS X is the HFS+ file system with journaling.

The original HFS (Hierarchical File System) dates back to the release of Apple’s first hard drive for the Macintosh in 1985. Replacing the previously used Macintosh File System, Apple kept HFS until 1998, when Mac OS 8.1 saw the introduction of the improved HFS+. But the real change came with the Server version of OS X 10.2.2 Jaguar, when HFS+ with journaling became optional, and 10.3 Panther, when it was turned on by default.

The file system is the low-level software, installed on a disk or other type of media, that catalogs and indexes the files on your computer. Without a file system, you can’t copy, move, or delete files. But when disk errors occur, or when a computer crashers, the file system’s catalog can get corrupted, and you may lose files. The data is still on your disk, but the file system can no longer find it.

Journaling uses a sort of log that keeps a record of changes before they are finalized. In the event of a crash, the disk can read the journal to ensure that no files are lost. As Apple explains:

“Journaling is a feature that helps protect the file system against power outages or hardware component failures, reducing the need for directory repairs.”

Do you remember having to regularly run disk repair software back in the day? Well, when Apple added journaling to its file system, this was no longer essential. (I can’t remember the last time I’ve lost files or data because of disk corruption or power outages.) Of course, hard disks can still fail, so you make sure you have backups.

System Integrity Protection

One of the newest security features is System Integrity Protection, or “Rootless.” On every Mac, there are a number of user accounts, including one called root, which is the “superuser,” the One Account to Rule Them All. The root user can do anything: access and modify or delete any file, change permissions for any user, and essentially screw things up if he or she makes a typo when futzing around in the operating system. Even a normal administrator can “play root” for a while, prefacing commands run in Terminal with the sudo, or “superuser do” command.

System Integrity Protection, introduced with OS X 10.11 El Capitan, prevents even this root user from accessing certain files. As Apple explains, “System Integrity Protection restricts the root account and limits the actions that the root user can perform on protected parts of OS X.” The goal of this is not to prevent any individual human user from accessing files, but rather to block malware that can “get root,” or obtain root access, and altering or damaging system files.

This doesn’t mean that these files are entirely off limit. As one would expect, certain tools can make changes to protected files. Apple elaborates on this, saying:

“System Integrity Protection is designed to allow modifications of these protected parts only by processes that are signed by Apple and have special entitlements to write to system files, like Apple software updates and Apple installers.”

There is, of course, a way to turn off System Integrity Protection and get full root access, and those system administrators who want to work without a net may want to find out how to to this. It’s not hard to do, but be aware of the risk it entails.

Computer security is complex, and there are many other under-the-hood features that keep OS X secure. Many of these features are added to Safari, since the web browser is one of the leading vectors of attack in our Internet age. The most important thing you can do to keep your Mac secure is to ensure your operating system and apps are up-to-date, so you benefit from all the latest security features and fixes.