Flashback to the Biggest Mac Malware Attack of All Time—Is it Still a Threat?

Posted on

by

Graham Cluley

In early 2012, the biggest Mac malware attack of all time was taking place – catching out at least 600,000 unguarded Mac users around the world, including (to potentially one famous company’s embarrassment) some 274 in Cupertino.

In early 2012, the biggest Mac malware attack of all time was taking place – catching out at least 600,000 unguarded Mac users around the world, including (to potentially one famous company’s embarrassment) some 274 in Cupertino.

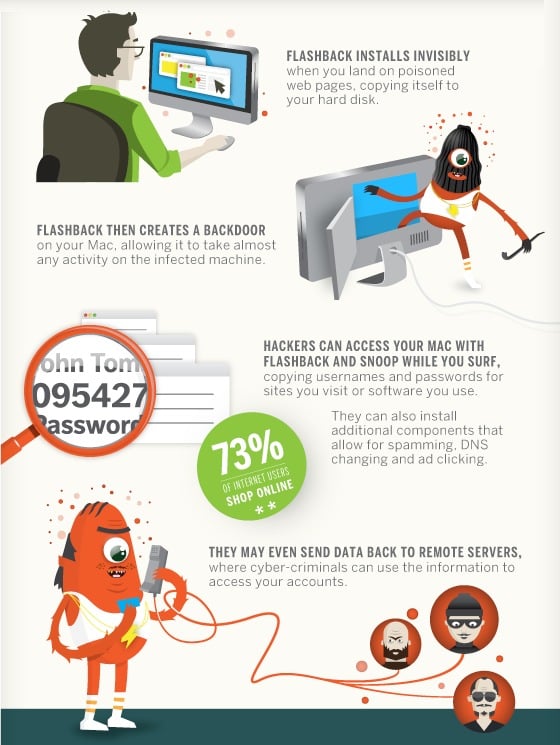

The Flashback malware posed as a bogus installer for Adobe Flash, exploiting a Java vulnerability to infect iMacs and MacBooks.

The truth is that Flashback should never have been able to spread at all. The drive-by download vulnerability in Java that Flashback relied upon had been patched by Oracle two months before… at least for Windows users.

Apple, unfortunately, had left Mac users vulnerable for more than six weeks – and only when the story of the major malware outbreak affecting Macs hit the headlines did they stir into action, and release a patched version of Java for Mac OS X users.

Subsequently, Apple realised the error of its ways and took the “nuclear” option of removing Java from the default installation of Mac OS X altogether, leaving it up to users to decide if they really wanted to install the software, which has been plagued with security holes in recent years.

Chances are that most of us thought that would be the end of the story for Flashback – with the only possible coda being the possible identification of whoever might have masterminded the hard-hitting malware outbreak attack.

With the lack of any arrests or prosecution, however, I thought it meant we probably wouldn’t be talking about Flashback again – and it would go down in the annals of cybercrime history as one of the reasons why Mac users finally worked up to the reality of malware threatening their computers.

Yes, Java vulnerabilities remain an issue – but Oracle is now responsible for patching those security holes for Mac users, and if you haven’t consciously chosen to install Java onto your computer, you shouldn’t have to lose any sleep about it.

But there remains evidence that Flashback remains a threat, even if it’s nothing like as big a problem as it was 18 months ago.

At the start of this year, Intego’s malware research team revealed that the Flashback botnet was still active, with some 22,000 infected computers still in its grasp. This meant that there were still opportunities for online criminals to exploit compromised Mac computers in order to send spam, steal information, or generate additional income by installing adware or redirecting web browsers.

And last week reports emerged that claimed US universities were riddled with old malware – including Flashback and the Windows Conficker worm.

Security firm BitSight decided to compare infections at large universities participating in the SEC, ACC, Pac-12, Big 10, Big 12 and Ivy League sporting conferences. In all, the firm claims to have covered 2.25 million students and 11 million IP addresses on college campuses. They reported the following:

Higher education institutions experience high levels of malware infections, the most prevalent infection coming from the Flashback malware, which targets Apple computers. Other prominent malware include Ad-ware and Conficker.

I spoke to Intego malware researcher Andrew Mitchell to see whether he felt we should still be fearful of Flashback, and why educational establishments might have been particularly troubled by the notorious malware.

I spoke to Intego malware researcher Andrew Mitchell to see whether he felt we should still be fearful of Flashback, and why educational establishments might have been particularly troubled by the notorious malware.

“Unlike the rest of the universities networks, dorm networks are often unsecured and open once you’re physically inside the dorm. In other words, once something gains access to one machine, it’s easy to find its way onto others,” began Mitchell.

“In addition, there are more old machines running there than elsewhere. Not every student can afford the latest and greatest laptop, and you’ll find more older machines in this population than elsewhere as families try to eek out the most from limited budgets.”

“Futhermore, many kids have never been responsible for updating their machines to the latest security updates, it’s been their parents’ responsibility, and now it’s up to them and they simply don’t worry about it.”

“Finally, we have to consider promiscuous computing,” the researcher quipped. “Kids are much more likely to share files, regardless of their origin, and as a result, this stuff spreads easily.”

But, it seems the Flashback problem isn’t one that should be troubling most of us.

Apple now offers free updates to its operating system, and Mitchell says that the only computers at risk from Flashback anymore are Power PC and first generation (non-64 bit) Intel-based Macs. The fact that Apple no longer distributes Java, and the decline in applications and websites that demand Java mean that less people are going to go to the effort to install it themselves.

In summary – yes, Flashback remains a threat. But for most of us, it’s a threat that we don’t have to worry about.

If you know someone who has an older Mac, or who is not likely to be doing a good job at keeping their computer protected with the latest patches and security software, be a good friend and offer them some help.

Together we can help to eradicate older threats like Flashback once and for all from the internet.